In a first-of-its-kind endeavor, AquaBounty farms country’s bio-engineered salmon in Indiana

Bio-engineered salmon, which grow at twice the rate of wild salmon, are the first genetically-engineered animals deemed safe to eat by the FDA.

Ten miles north of Muncie, a new 40-acre farm is busy with work — all day and all night. What’s being grown there, though, isn’t what most would likely expect from Hoosier farm country.

Just outside Albany, the gate-restricted, mostly inconspicuous facility owned by AquaBounty Technologies is one of few aquaculture farms in the state. Indoors, thousands of salmon swim within large, 70,000-gallon tanks. They’re eating and growing, being monitored by farm hands and biologists around the clock.

But a new, brimming batch of eggs are different than those already swimming around.

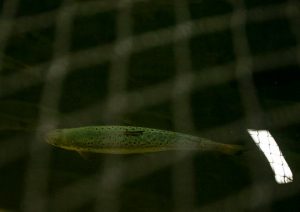

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm farm manager Peter Bowyer points out the small salmon raised on the farm in Albany, Indiana, Thursday, June 27, 2019. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm farm manager Peter Bowyer points out the small salmon raised on the farm in Albany, Indiana, Thursday, June 27, 2019. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

Growing at twice the rate of wild salmon, these are the first genetically-engineered animals deemed safe to eat by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Their existence in Indiana also marks the first time a genetically-modified food animal will be raised and sold in the United States.

The salmon are expected to hit the U.S. market next year, but their consumer success remains to be determined. AquaBounty and the FDA persist that the fish are safe to eat. Scientists say the biotechnology used could help the industry meet growing seafood demands.

Will salmon-lovers bite, too?

Raising fish in the Heartland

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

On a hot, muggy day in late June, farm manager Peter Bowyer walked the grounds of the Albany salmon facility — a time consuming task. Each entrance into a different area of the farm requires a change into clean clothes, swapping out boots, a walk through a foot bath and a generous amount of hand sanitizer. Bio-security is important here, Bowyer says: “We don’t want anything from the outside coming in … and we don’t want any fish going out.”

Once inside a dimly-lit building on the property, Bowyer points out an incubator. Within the device, 12 trays — each with anywhere from 8,000-8,700 salmon eggs — are being kept at a “cozy” 45.5 degrees. They’ll stay here in the hatchery for several weeks before heading to the nursery and later to the tanks.

These salmon, still no larger than a fingernail, were developed by adding a growth hormone-regulating gene from Pacific Chinook salmon, along with a promoter gene from an ocean pout, to the Atlantic salmon’s genes.

The fish, coined AquaAdvantage salmon, are engineered to grow faster than their non-genetically modified counterparts: the gene alteration means the fish eat 25 percent less feed and reach market size (about 10 pounds) in half the time — roughly 18 months.

“The difference biologically is just a gene,” said Bowyer, who holds a doctorate in aquaculture nutrition. “Today, the breeding process to yield the eggs here is no different than the process that any other salmon producer around the world would employ.”

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

The salmon in Albany are also all sterile females, Bowyer said. It’s another bio-control caution. In the off-chance that one escapes the facility, the salmon can’t breed with other fish in the local waterways. In case any eggs escape, chlorine is also used to clean drains. Numerous layers of screens, filters and nets in pipes and around the facility help, too.

Fish waste is handled a bit differently. When it exits the facility, water waste is discharged into on-site filtration ponds. The solid leftovers, on the other hand, are collected and used by local farmers as fertilizer.

“It’s another reason why Indiana and all its crop production is convenient for this kind of thing,” Bowyer said.

More than a dozen academic and scientific journal articles have outlined and applauded the environmental and commercial benefits of these engineered, indoor farmed salmon operations. But getting the fish to Indiana — and getting consumers on board — has been coupled with obstacles.

The ‘biotech’ approval hurdle

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm farm manager Peter Bowyer puts on gloves in the hatchery room, Albany, Indiana, Thursday, June 27, 2019. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm farm manager Peter Bowyer puts on gloves in the hatchery room, Albany, Indiana, Thursday, June 27, 2019. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty, headquartered in Maynard, Massachusetts, developed the genetically engineered fish in 1989 to grow more rapidly than wild salmon.

The company received approval from the Canadian government for commercial production of the salmon eggs in 2013. Additional approval from Canada’s Food Inspection Agency in 2016 meant the fish could be sold and consumed, and a year later, AquaBounty reported they had sold more than four tons of AquaAdvantage salmon fillets to Canadian customers.

The process wasn’t so easy in the U.S.

Here, AquAdvantage salmon need to pass two assessments: one to determine the safety of a new “animal drug” entering the food supply (new genes and gene products in genetically engineered animals are regulated as such by the FDA), and another assessing potential risk to the environment.

Initial FDA approval for AquAdvantage salmon to be produced in Panama and Canada came in 2015 — 20 years after the agency started its review. A secondary application for AquaBounty to raise the salmon in Albany was approved in April 2018.

In published findings, the FDA came to the conclusion that “the salmon are safe to eat.” The introduced DNA is “safe for the fish itself,” the agency added, and the nutritional profile of AquAdvantage salmon “is comparable to that of non-GE farm-raised Atlantic salmon.”

Based on the “multiple forms” of physical and biological containment AquaBounty proposed for its Indiana facility, the FDA also found the salmon would not cause a significant impact on the environment. The likelihood that AquAdvantage salmon could escape into the surrounding environment is “extremely low, according to the FDA. Even if they did, conditions around the Indiana site are too “hostile” for the salmon’s long-term survival.

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

“Indiana is actually a good location because it’s landlocked … the salmon are very unlikely to escape or do harm,” said Sylvia Wulf, CEO of AquaBounty Technologies. “That’s one of the reasons we choose [Albany].”

But even after facility approval, AquaBounty was still prohibited from importing the AquaAdvantage eggs due to an appropriations law, blocking the salmon into the market until the government published labeling guidelines for bio-engineered products. The U.S. Department of Agriculture released those standards in December 2018, and the import alert was deactivated in March 2019.

Still, several more months were required for AquaBounty to receive the necessary permits to ship eggs from its Prince Edward Island hatchery. With that final step complete, the first shipment — containing some 90,000 eggs — cleared inspections at Chicago O’Hare Airport and made its way to Albany in May.

“It did take a long time to get to this point,” Wulf said. “But we think there’s a lot of potential with this salmon — to help feed a lot of people — and that consumers are going to really like it. So, it’s worth it.”

And demand for salmon is increasing.

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm CEO and President Sylvia Wulf smiles during an interview Thursday, June 27, 2019, Albany, Indiana. AquaBounty is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm CEO and President Sylvia Wulf smiles during an interview Thursday, June 27, 2019, Albany, Indiana. AquaBounty is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

In 2018, the U.S. imported more than 400,000 metric tons of all types of salmon, a value exceeding $4.1 billion, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service. For Atlantic salmon in particular, some 327,000 metric tons valued at more than $3.4 billion were brought into the country last year.

Given the fish’s lauded nutritional benefits, experts also point to salmon as a healthy way to meet a growing, and hungry, global population.

Meeting consumer appetites for salmon, however, has proved challenging for the aquaculture industry. Wild stocks, vulnerable to over-fishing and rising water temperatures, aren’t enough. Salmon farming powerhouses in Norway and Chile, where fish are often raised in sea pens, have also been criticized for massive fish escapes, water pollution issues and overuse of antibiotics.

Globally, the U.S. remains a relatively minor aquaculture producer, and nearly 90 percent of the seafood Americans eat comes from abroad as a result.

“We need to think about science as a way of helping us combat climate change and as a way to help us feed people sustainably,” Wulf said. “There’s an opportunity to do that with our salmon, and that’s what we’re striving to do.”

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

‘It’s still the same salmon’

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch — an authority on sustainable seafood —uses a traffic light system to rate fish from most to least recommended for consumers.

Indoor farmed salmon (and by extension, genetically-engineered salmon) are a Seafood Watch “Best Choice.” Indoor recirculating tanks often have less waste, disease, escapes and habitat impacts than other aquaculture systems, the nonprofit organization says, steering consumers away from farmed Atlantic salmon and instead praising land-based operations. Currently, only 0.1 percent of farmed Atlantic salmon is produced using the indoor method.

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

Much of the Atlantic salmon farmed in Canada’s Atlantic coastlines, Chile, Norway and Scotland are on the Seafood Watch “Avoid” list. The overuse of chemicals and escapes of farmed salmon into the wild are the primary reasons cited for the unfavorable rating.

“Salmon industry (operations) across the world all have different challenges. Ours, in Indiana, are just more unique,” said Alejandro Rojas, AquaBounty’s chief operating officer, who’s spent 30 years working in aquaculture. “One of the biggest we face is with consumers and helping them understand our product. It’s still the same salmon, we’re just farming it in a new way.”

And there are critics.

The Center for Food Safety, an environmental nonprofit, has advocated against U.S. retailers selling the fish and instead is calling for more focus on wild salmon populations. Costco, Kroger and dozens of other supermarket chains have agreed not to sell the fish, according to the Center. The nonprofit is also one of several organizations that are suing the FDA, arguing that the federal agency didn’t have the authority to approve genetically-engineered animals for food in the first place.

The International Salmon Farmers Association further told USA Today there’s “probably nothing” wrong with genetically engineered salmon, but there’s still fear about how the public will perceive the AquAdvantage fish — and what that could do to the industry overall.

“It will destroy the reputation of the salmon. This is not good PR for the salmon business. It’s considered Frankenstein fish,” president Trond Davidsen said in March. “If you’re being rational, that’s not the case, but that’s the image that’s already been produced.”

The FDA’s public comment call for the AquAdvantage regulatory approval application additionally elicited more than 360,000 comments, with some commenters taking issue with potential environmental impacts, fish quality and feared human health effects.

But others say the contention is almost expected. In their 2018 Animal Biotechnologyarticle, researchers at the University of California, Davis say new technologies like this are “frequently met with suspicion or hostility” because they’re often hard to understand or associated with complicated scientific principles.

“Clearly, the use of genetically-engineered animals for food is a controversial topic,” the researchers wrote, adding that AquAdvantage’s commercial “success or failure will [still] truly be up to the public.”

Farm to table

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaBounty Technologies Salmon Farm in Albany, Indiana, is the first land-based fish farm to raise genetically modified Salmon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015 and now the AquaBounty is looking to begin selling their products to the U.S. “We’re gonna have to start changing the way we are thinking about science… We need to think about science as a way to help us with things like climate change and feeding people,” said President and CEO of Aquabounty Technologies Salmon Farm Sylvia Wulf. (Photo: Grace Hollars/IndyStar)

AquaAdvantage fish could be ready to hit the market by 2020, Wulf said. Although none of the salmon has been sold in the U.S. yet, Wulf added that the fish might first be sold in restaurants or university cafeterias.

The new USDA law for product labeling directs companies to disclose the presence of genetically-modified ingredients in food products through the use of either a QR code, an on-package display of text or a designated symbol. Mandatory compliance with that regulation is set to take full effect in January 2022, but the rules don’t apply to restaurants or food service venues.

Wulf said AquaBounty plans to voluntarily use “bio-engineered food” labeling on its packaging when the fish are ready to be sold. That’s because the company “is all about transparency,” Wulf said, given its confidence that AquaAdvantage salmon “can solve a lot of problems.”

“We want consumers to know where their food came from and how it was raised,” she said. “We have nothing to hide. We’ll do whatever customers want us to do.”

At full capacity, the Albany facility is expected to harvest approximately 90 metric tons of salmon per month. This meets less than 1 percent of the U.S. demand, but Wulf said that with a positive consumer response, AquaBounty might request approval for more facilities from the FDA.

“I’m confident that once we help consumers understand that safety and impact on the environment should not be a concern, and that using science and technology to solve global challenges makes a lot of sense, there won’t be as many worries,” Wulf said. “And as long as it’s within the guidelines and guardrails of good regulatory process, consumers shouldn’t be worried about genetically modified food.”

Call IndyStar reporter Casey Smith at 317-444-6176 or email her at casmith@indystar.com. Follow her on Twitter @SmithCaseyA.